Concrete Applications of Geothermal Energy

Introduction

Geothermal energy, often unknown to the general public, nonetheless represents an energy solution in full expansion across the world. Far from being limited to Icelandic volcanoes or California geysers, this natural resource today finds concrete applications in fields as varied as residential heating, agriculture, or industrial production.

The latest global data reveals continuous growth of this technology, even if it remains modest compared to other renewable energies. According to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), the total installed capacity of geothermal energy reached approximately 15.4 GW at the end of 2024, an increase from about 13.0 GW recorded at the end of 2020; net growth during 2024 was limited, with only about 0.4 GW of new capacity added. [13] This expansion demonstrates a global awareness of the potential of this renewable energy.

Beyond installed volumes, geothermal energy is distinguished by the diversity of its uses. Geothermal heat pumps represent approximately 58.8% of total use, followed by bathing and swimming (18%), space heating (16%, of which 91% for district heating), greenhouse heating (3.5%), industrial applications (1.6%), aquaculture (1.3%), agricultural drying (0.4%), as well as snow melting and cooling (0.2%) [1].

This distribution highlights the versatile nature of geothermal energy and its integration into very different sectors. This article proposes to examine these main uses, illustrating, through concrete examples, the way in which geothermal energy is today mobilized to meet residential, agricultural, industrial, and urban energy needs.

District Heating: The Emblematic Example of Iceland

When discussing geothermal district heating, Iceland naturally stands out as an essential reference. The country has been able to take advantage of an abundant local resource to build an energy system that is simultaneously reliable, sustainable, and widely accepted by the population. Today, approximately 90% of the energy used for domestic heating in Iceland comes from geothermal energy (2020), a percentage unique in the world that continues to grow [2].

At the heart of this success, Reykjavík's district heating system occupies a central place. It is among the largest and most efficient in the world. At the national level, 22 public or municipal geothermal heating companies operate 62 distinct networks. The largest feeds the capital Reykjavík as well as five neighboring communities, providing heat to more than 180,000 inhabitants and consuming approximately 12 PJ per year [3].

The scale of the infrastructure is impressive, but it is especially its efficiency that captures attention. The Reykjavík network distributes nearly 75 million cubic meters of hot water to approximately 200,000 people each year. This heat comes from 52 geothermal wells, delivering together 2,400 liters per second of water at temperatures between 62 and 132°C [4]. These figures concretely illustrate the technical and economic viability of large-scale geothermal heating.

More broadly, the Icelandic experience demonstrates that a coherent strategy around geothermal energy can profoundly transform a country's energy mix. The Reykjavík model today inspires many cities around the world, showing that geothermal district heating constitutes a credible alternative to fossil fuels, provided that resources are accessible.

Finally, it would be reductive to think that this success only concerns cold regions. This energy finds equally relevant applications in temperate and even tropical climates, as we will see in the following sections.

Geothermal Heat Pumps: A Silent Revolution

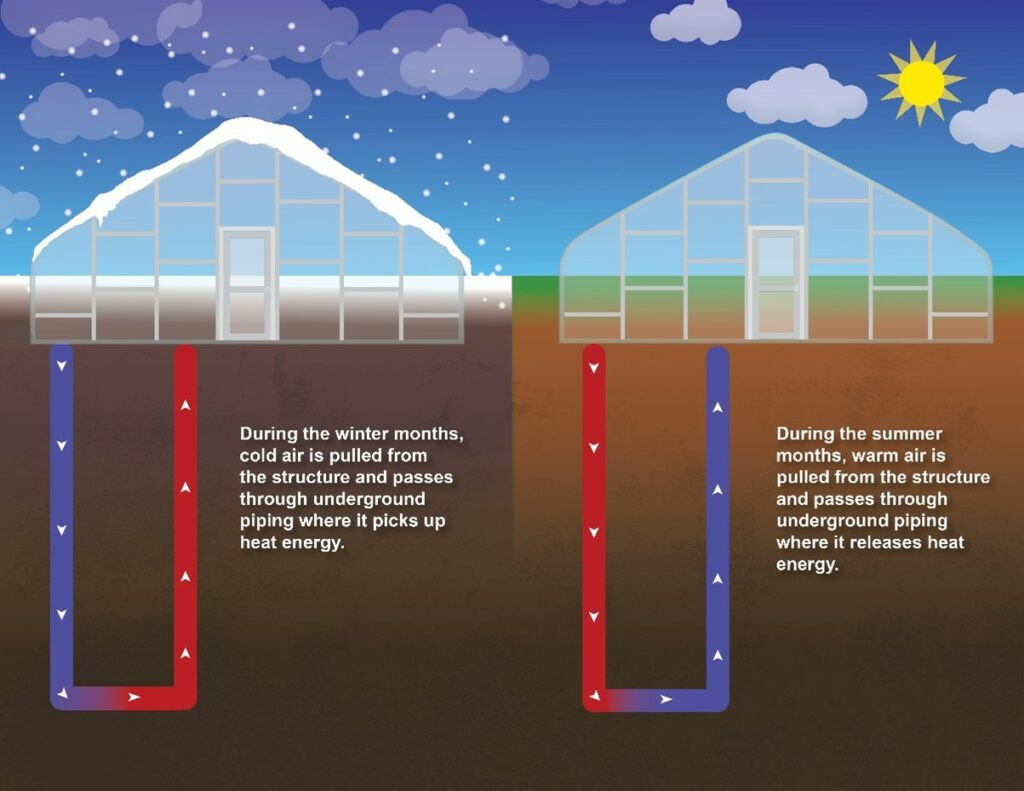

Geothermal heat pumps represent the most widespread geothermal technology globally, revolutionizing residential and commercial heating and cooling. This technology exploits the stable temperature of the subsoil to heat in winter and cool in summer, offering remarkable energy efficiency.

Moreover, geothermal heat pumps use 75% less energy than traditional heating and cooling systems [5]. This exceptional efficiency translates into substantial savings on energy bills and a significant reduction in the carbon footprint of buildings.

Practical applications of this technology are multiplying across North America. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) has documented 19 real-world case studies of geothermal heat pumps in action in the United States [6], demonstrating their adaptability to various climatic conditions and building types, from single-family residences to commercial complexes.

Source: ATTRA Sustainable Agriculture

The operating principle is based on thermal exchange with the soil, which maintains a relatively constant temperature throughout the year. In winter, the system extracts heat from the soil to heat the building; in summer, it rejects excess heat into the soil to cool. This reversibility makes geothermal heat pumps a complete solution for the thermal comfort of buildings.

The growing adoption of this technology is explained by several advantages: durability (systems can operate for 25 years or more), low operating costs, minimal maintenance, and no on-site combustion. These characteristics make it a particularly attractive solution for owners concerned about reducing their environmental impact while controlling their long-term energy costs.

Agriculture and Geothermal Greenhouses: Feeding the World Sustainably

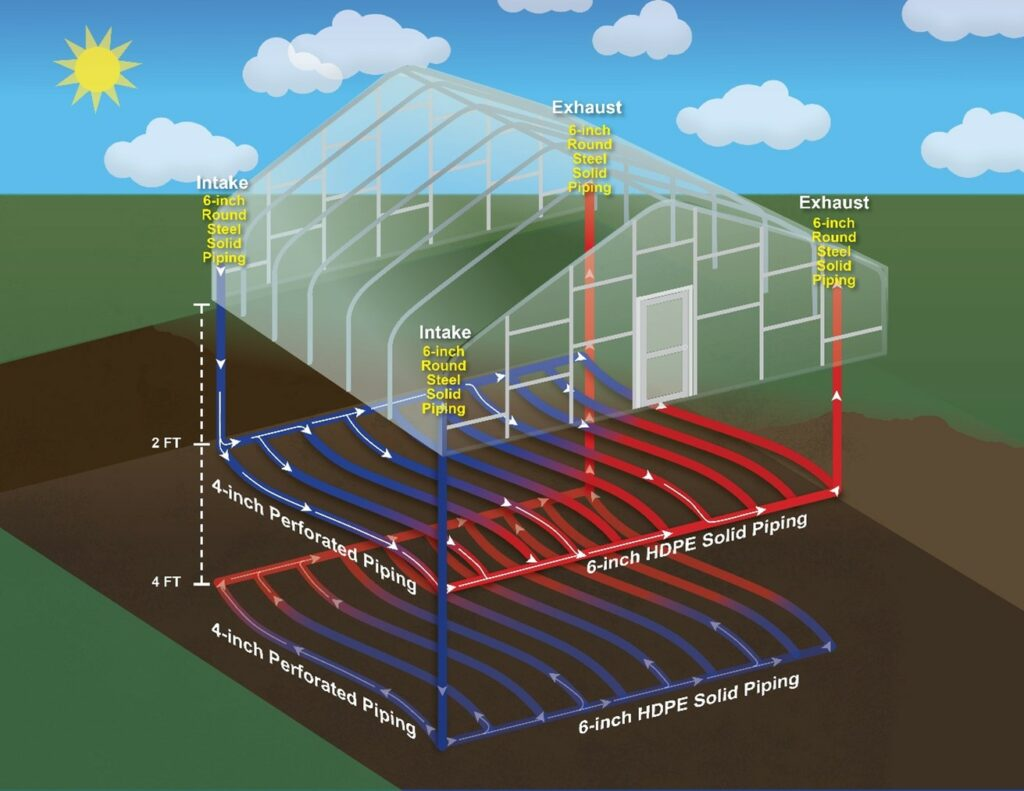

In a context of growing pressure on food systems, geothermal agriculture opens particularly promising perspectives. By providing a stable and continuous heat source, it enables year-round production, regardless of seasons and climatic hazards. This approach profoundly transforms greenhouse cultivation and horticulture, strengthening both the resilience and sustainability of operations.

The use of cultivation infrastructures heated by geothermal energy plays a key role in extending production seasons. By greatly reducing dependence on conventional energies such as oil or gas, geothermal heating and cooling systems help reduce greenhouse gas emissions and air pollutants. This reduced energy dependence not only improves the environmental balance of operations but also strengthens their long-term economic stability [7].

Around the world, several concrete initiatives already illustrate this potential. In Kenya, for example, the Oserien company has been using geothermal energy since 2003 for the production of flowers for export [8]. This experience demonstrates that it is possible to reconcile large-scale commercial agriculture with environmental protection, while maintaining high competitiveness.

In the United States, geothermal energy is already used for greenhouse cultivation, food drying, and the raising of catfish and crocodiles. The consistent and predictable heat offers obvious advantages for temperature regulation in fish farming operations [9]. These diverse uses demonstrate the adaptability of geothermal energy to very different agricultural and aquacultural needs.

It is also worth noting that this energy is particularly suited to contexts where conventional production methods reach their limits. The ability to maintain optimal growing conditions, regardless of external weather conditions, allows producers to expand their production range and better meet market demands. In the long term, this approach can also contribute to reducing food dependency on distant imports.

Beyond cultivation, geothermal energy opens up prospects for processing agricultural products directly on site. Drying, pasteurization, or even sterilization can benefit from this sustainable heat, thereby reducing the carbon footprint of the entire production chain. Such integration strengthens the overall viability of geothermal operations while better valorizing local resources.

Source: ATTRA Sustainable Agriculture

Industrial Production: Heat as a Production Tool

Industry, long dependent on fossil fuels to cover its energy needs, is gradually discovering the benefits of geothermal energy. This transition is motivated by both economic and environmental concerns. In contexts where industrial heat is required at moderate temperatures, geothermal energy offers a viable and sustainable alternative that also improves the competitiveness of companies.

Among the most emblematic examples, the extraction and processing of lithium stand out. Companies are exploring the use of geothermal brines to produce lithium, an essential material for battery manufacturing. This approach combines mineral resource exploitation with sustainable energy production, illustrating the potential for synergies between the mining and geothermal sectors [11].

In practice, industrial drying also constitutes one of the most widespread uses. Geothermal heat allows efficient and controlled dehydration of fruits, vegetables, and other agricultural products. In addition to significantly reducing energy needs, this method contributes to better nutrient preservation compared to conventional techniques.

Geothermal pasteurization also offers notable advantages for the dairy industry. By relying on the natural heat of the subsoil, producers can treat milk without resorting to fossil fuels. This approach reduces operating costs while meeting growing consumer expectations regarding sustainability and environmental responsibility.

Ambient Temperature District Systems: Innovation for Tomorrow

As cities seek to reconcile decarbonization, resilience, and cost control, ambient temperature district systems are emerging as a particularly promising avenue. Often presented as the next step in geothermal innovation, this approach fundamentally rethinks the way thermal energy is produced, shared, and used at the urban scale. It combines the intrinsic efficiency of geothermal energy with the flexibility of modern thermal networks.

Ambient temperature districts are considered to have equal or greater potential to reduce the load on the electrical grid compared to individual geothermal heat pumps, leading to significant savings in network costs [12]. This collective approach optimizes the use of geothermal resources while minimizing individual investments.

These systems work by distributing water at a temperature close to that of the ground (generally between 10 and 25°C) through a network of pipes. Each connected building then uses heat pumps to raise or lower this temperature according to its specific needs. This architecture allows great flexibility: some buildings can heat while others cool, creating energy synergies at the district level.

One of the main advantages of these districts lies in their ability to reduce peak demand on the electrical grid. By smoothing energy needs and facilitating heat transfers between users, they reduce pressure on existing infrastructures. For municipalities and network managers, this translates into a concrete opportunity to delay, or even avoid, heavy investments in electrical network expansion.

Current pilot projects confirm the relevance of this approach in a wide variety of urban contexts. Whether for university campuses, new residential neighborhoods, or mixed-use areas, ambient temperature districts offer a scalable solution to support the energy transition of cities. Their efficiency is particularly marked in environments combining residential, commercial, and institutional uses, where the diversity of consumption profiles maximizes energy synergies.

An Energy Future Anchored in the Earth

The analysis of concrete applications of geothermal energy highlights a potential that is still largely untapped. From Icelandic district heating powering nearly 90% of homes to geothermal greenhouses in Kenya, through heat pumps capable of greatly reducing the energy consumption of buildings, this energy demonstrates its versatility and effectiveness in very varied contexts.

For the mining industry, the convergence with geothermal energy opens particularly promising prospects. Data from exploration can reveal unsuspected geothermal resources, offering opportunities for diversification and valorization of existing assets. Actors who engage in this path thus position themselves at the heart of the energy transition.

More broadly, geothermal energy appears as a mature, reliable, and scalable energy solution. It provides concrete answers to climate challenges while supporting economic development and energy security. Thus, for decision-makers and actors in the energy transition, geothermal energy constitutes a clean, continuous, and sustainable resource that deserves to be fully taken into account in long-term energy strategies.

References

[1] Lund, John W., and Aniko N. Toth. "Direct utilization of geothermal energy 2020 worldwide review." Geothermics, vol. 90, 2021, 101915. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0375650520302078

[2] Orkustofnun (National Energy Authority of Iceland). "District Heating." Natural Resources, 2020. https://orkustofnun.is/en/natural_resources/district_heating

[3] Ragnarsson, Árni. "Geothermal development in Iceland 2005-2009." Geothermics, vol. 40, no. 1, 2011, pp. 1-8. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0375650510000416

[4] International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). "Overview - Energy Market - Geothermal Energy - Iceland." Regional Focus Presentation, May 2020. https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Presentations/Regional-focus/2020/May/Overview--Energy-Market--Geothermal-Energy--Iceland.pdf

[5] Center for Sustainable Systems, University of Michigan. "Geothermal Energy Factsheet." CSS Publications, 2023. https://css.umich.edu/publications/factsheets/energy/geothermal-energy-factsheet

[6] National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). "19 Real-World Examples of Geothermal Heat Pumps in Action." NREL News, 2024. https://www.nrel.gov/news/detail/program/2024/19-real-world-examples-of-geothermal-heat-pumps-in-action/

[7] National Center for Appropriate Technology (NCAT). "Geothermal Greenhouses: Exploring the Potential." ATTRA Publications, 2023. https://attra.ncat.org/publication/geothermal-greenhouses-exploring-the-potential/

[8] AgriTech Tomorrow. "Applications of Geothermal Energy for Agriculture." AgriTech Tomorrow, September 2022. https://www.agritechtomorrow.com/story/2022/09/applications-of-geothermal-energy-for-agriculture/14069/

[9] U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). "Use of Geothermal Energy." Energy Explained, 2024. https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/geothermal/use-of-geothermal-energy.php

[10] ThinkGeoEnergy. "ThinkGeoEnergy's Top 10 Geothermal Countries 2024 – Power Generation Capacity." ThinkGeoEnergy, 2024. https://www.thinkgeoenergy.com/thinkgeoenergys-top-10-geothermal-countries-2024-power/

[11] National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). "Exploring Synergies Between the Geothermal and Mining Industries: A Roadmap for Leveraging Existing Data, Infrastructure, and Operational Expertise." NREL Technical Report, NREL/TP-5700-81946, 2022. https://docs.nrel.gov/docs/fy22osti/81946.pdf

[12] National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). "National Modeling of Geothermal District Energy Systems." NREL Technical Report, NREL/TP-5700-90324, 2025. https://docs.nrel.gov/docs/fy25osti/90324.pdf

[13] International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Geothermal Energy. IRENA, n.d., https://www.irena.org/Energy-Transition/Technology/Geothermal-energy